Just as few people appreciate the Civil War history that Southwest Virginia has to offer, even fewer know the region’s African American history. These sites tell a broad story of the African American experience, speaking on themes such as slavery, freedom, justice, violence, education, and politics. These sites reflect a long timeline, from Smithfield, a plantation built by enslaved labor in the 18th century, to the Christiansburg Institute, a school for newly freed slaves founded in the late 1860s which closed 100 years later following the desegregation of schools. Most of all, these sites all speak to the importance, presence, and power of Southwest Virginia’s African American history. As Karri Moseley-Hobbs, a descendant of one of Smithfield Plantation’s enslaved families, said at a building dedication in April of this year, “We were here and we are here.” This tour will take you through almost 200 years of African American history in Southwest Virginia, revealing moments of struggle, pain, frustration, and violence, but also of joy, victory, community, and activism.

Kentland Plantation Slave Cemetery

5250 Whitethorne Road, Blacksburg

A large plantation prior to the Civil War, Kentland was built and maintained by over 100 slaves. When the war came to Kentland, many of these slaves escaped to freedom. After the war, owner James Randal Kent’s wife Elizabeth established the Wake Forest community for freed slaves. The old Kentland slave cemetery has recently been rediscovered and is now marked. Click here to learn more about the plantation and the enslaved people who lived and worked there.

Historic Smithfield

1000 Smithfield Plantation Road, Blacksburg

Once a thriving plantation, the history of Smithfield is also the history of the people who were enslaved there. Two of these slaves, Thomas and Othello Fraction, escaped the plantation during the war to join the United States Colored Troops. Following the war, the two man attempted to visit their family who were still at Smithfield, which resulted in their arrest. Click here to learn more about Historic Smithfield and here to learn more about the Fraction brothers.

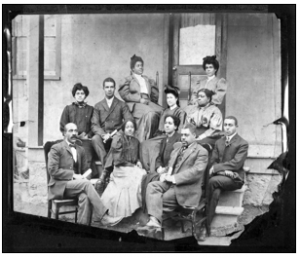

Christiansburg Institute

1400 Scattergood Drive NW, Christiansburg

Founded in the years following the Civil War, Christiansburg Institute was designed to educate newly freed slaves. In 1869, Booker T. Washington became the school’s adviser, inspiring them to adopt a curriculum similar to that of Tuskegee and Hampton Institutes. The school stayed open until the integration of schools in 1966. Click here to learn more about the Christiansburg Institute.

Wytheville

410 East Franklin Street, Wytheville

Begun as four-room school and church immediately after the Civil War, the Wytheville Training School Cultural Center now preserves and interprets the historic Wytheville Training School, a school for freed slaves. The Center served as a gathering place for the African American community of Wytheville and surrounding counties into the 20th century until it was closed in 1952. Click here to learn more about Wytheville during and after the Civil War.

Saltville

123 Palmer Avenue, Saltville

As a production center of salt for the Confederacy, Saltville was a target for a few largely unsuccessful Union raids in the area. After a Union defeat near the town in October 1864, a Confederate troops massacred wounded African American soldiers who had been left on the battlefield. Camp Nelson National Monument, a National Park Service site that interprets the Union base where the African American soliders originated from, commemorates the massacre here. Click here to learn more about Saltville’s Civil War sites.

Abingdon

Intersection of A Street SE & Tanner Street SE, Abingdon

Landon Boyd is the subject of one of Abingdon’s first Civil War Trails markers. Born into slavery in Abingdon in 1838, Boyd may have served in the Union Army and after the war, he was chosen for the jury assigned to the 1867 trial of Confederate president Jefferson Davis. He became a prominent resident of Richmond, Va. throughout the 1870s before returning to Abingdon. He is buried in Abingdon’s Sinking Spring Cemetery. Click here to learn more about Abingdon and Boyd’s experience of the war.

Bonus Sites

Appalachian African-American Cultural Center

230 North Leona Street, Pennington Gap

Housed in a building that was once a school for the African American community of Pennington Gap, The Appalachian African-American Cultural Center offers a library of black literature and hosts events such as Race Unity Day and workshops on racism and racial issues.

Harrison Museum of African American Culture

523 Harrison Avenue NW, Roanoke

Also based out of a former school for African American students, this museum presents artifacts, photographs, and art that share the experience of the African American community in the Roanoke Valley. The museum also sponsors the annual Henry Street Heritage Festival.

Historic Pulaski County Courthouse & Museum

52 West Main Street, Pulaski

Inside this beautiful building is a museum exhibit on the local African American history, developed by Lucy Harmon, an early civil rights advocate in the 1950s.

Want to learn more about African American history?

African American Soldiers

“Black Civil War Soldiers,” published by HISTORY, August 21, 2018.

William A. Dobak, Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867. New York: Skyhorse, 2013.

Barbara A. Gannon, “African American Soldiers,” in the Essential Civil War Curriculum.

Thomas D. Mays, The Saltville Massacre, Abilene, Texas: McWhiney Foundation Press, 1998.

African Americans in Appalachia

John C. Inscoe, ed. Appalachians and Race: The Mountain South from Slavery to Segregation, Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2001.

Althea Webb, “African Americans in Appalachia,” published by Oxford African American Studies Center.

William H. Turner and Edward J. Cabbell, eds. Blacks in Appalachia. Lexington, KY: The University of Press of Kentucky, 1985.

The Freedman’s Bureau & African American Schools

W.E.B. DuBois, The Education of Black People, New York: Monthly Review Press, 2001.

“Industrial Training for African Americans,” published by Encyclopedia.com, 1997.

“Freedman’s Bureau,” published by HISTORY, October 3, 2018.