By Eleanor Boggs and Jacob Clore

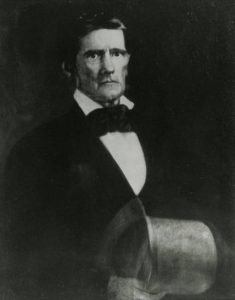

- Born at the Breckinridge family home in Cabell’s Dell, Kentucky on March 8th, 1800.

- Graduated from Union College in 1819.

- Elected in 1825 to Kentucky House of Legislature.

- Converted to Presbyterianism in 1829 and ordained as a minister of the same faith in 1832.

- Professor at the Danville Theological Seminary from 1853 until 1869.

- Died in Danville, Kentucky on December 27th, 1871.

Robert J. Breckinridge was born on March 8th, 1800 to Mary Hopkins Breckinridge and Senator John Breckinridge of Kentucky. He had a rather rebellious childhood, including during his college years. He married his second cousin Ann Sophonisba Preston in March of 1823, establishing firm ties between two powerful southern families. After her death in 1844, Breckinridge would have two subsequent marriages, to Virginia Hart Shelby and Margaret Faulkner White.

In 1829, Breckinridge’s life changed drastically due to a personal illness and the death of his daughter. As a result of the major life changes, he converted to Presbyterianism in 1829 and was ordained as a minister in 1832. He also spent much of his adult life fighting for causes he was passionate for. Prior to the Civil War, he was a slaveholder and a critic of slavery; an interesting combination. In the late 1840s and early 1850s, he served as Kentucky’s state superintendent and made public education more of a priority during his tenure. During the Civil War, he focused more of his attention on maintaining the Union and gave many speeches indicating why secession was bad for the nation.

A Man of Faith

Robert J. Breckinridge became a minister for the Presbyterian Church in the 1830s. Around the same time, the Church was dividing into two schools of thought: the Old School, which upheld the original Calvinist theology and rejected revivalism, and the New School, which embraced emotional revivalism, which was a form of Christian activism. Breckinridge aligned himself with the Old School. In fact, he was instrumental in the schism: he drafted the “Act and Testimony,” which outlined the differences between the Old School and the New School.

The schism solidified Breckinridge’s political views as well as his faith. As a member of the Old School, Breckinridge firmly believed in predestination and his role as one of God’s chosen. He justified his political positions as a pro-Unionist and gradual emancipationist through the doctrine of the Presbyterian Church. He was entirely confident in his moral rightness; he believed that God supported his words and his actions. Breckinridge’s absolute certainty in his faith carried over into his views on slavery and Unionism.

A Slaveholder against Slavery

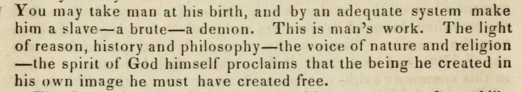

Breckinridge’s personal philosophy and religious views conflicted with the kind of slavery the southern states practiced. He believed that God created everyone free, however, that did not mean that God created everyone of every race and gender equally. He argued specifically for a gradual emancipation of slaves, so that the change would not come as too much of a disruption for both the owners and the slaves themselves.

His dedication to the abolitionist cause took him all the way to Europe, where he explained his views on slavery and learned from others what their philosophies were. In 1836, he engaged in a debate with a Scottish man by the name of George Thompson. Throughout the debate, Breckinridge argued that abolitionists should not identify with any group or party when fighting against slavery. He did not want sectionalism and division to disrupt a noble cause. He also wanted abolitionists to fight against slavery with a Christian spirit and the spirit of the Gospel.

During the late 1850s and 1860s, Breckinridge focused more attention on the secession crisis and less on criticism of slavery. During his years fighting for the Union, he referenced slavery mostly in economic and political terms, to downplay its moral importance so he could focus more on the Union. He also took more of a neutral stance with the religious aspects of slavery, stating that the Bible did not state whether the practice of slavery was immoral or not.

Changes in the 1850s

While Breckinridge passionately expressed his criticisms of slavery during the 1830s and 1840s, he did not have the same zeal for the cause during the rest of his life. During the late 1840s and 1850s, Breckinridge had a tumultuous life, both personally and professionally. He was distracted by family problems, his extensive book writing, his work with the Know-Nothing Party, and his work towards public education. From 1847 to 1853, Breckinridge served as Kentucky’s sixth state superintendent of public education. Breckinridge believed that all children should attend school and he would feel satisfied if he had achieved that goal. Sure enough, he fought successfully for a two-cent property tax for education purposes. Breckinridge’s efforts also led to an increase in spending on education in Kentucky, from $6,000 in 1847 to $144,000 by 1850. By the end of his term, Breckinridge helped to improve the image of education among the public. His rigorous support for education, other political crusades, and personal issues quickly overcame his crusade against slavery.

A Proud Unionist

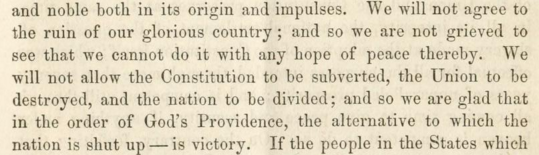

By 1860, Breckinridge was facing a different set of issues. With the Civil War and the continued division between the North and South, Breckinridge focused on unifying the nation. As with his work against the long-term survival of slavery, Breckinridge used his religion as an inspiration for his unionist work. Throughout many of his writings, he referenced secession as humiliating in front of the Lord. He also believed that the strife the nation faced was a result of national sins.

Breckinridge believed that the South’s secession was an outright denial of God’s destiny for the United States. He viewed the Civil War as a test of God’s providence and the nation’s destiny. Breckinridge maintained that the Union would ultimately defeat the Confederacy and reabsorb the South. His confidence in the North and his view of the nation’s destiny reveals how religion mixed with his political loyalty to the Union.

Further Reading

Collection of Robert J. Breckinridge’s publications at Internet Archive

Biography on Robert J. Breckinridge by Dr. Barry Waugh

Collins, Lewis and Richard Henry Collins, “Historical Sketch of the Presbyterian Church,” Collins’ Historical Sketches of Kentucky: History of Kentucky, Volume I, Collins & Company, 1882.

Doherty, Robert W., “Social Bases for the Presbyterian Schism of 1837-1838: The Philadelphia Case,” Journal of Social History, Vol. 2, Oxford University Press, 1968, 70.

Klotter, James C. The Breckinridges of Kentucky. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1986.

Rable, George C. God’s Almost Chosen Peoples: A Religious History of the American Civil War. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Thompson, George; Breckinridge, Robert J.; Burleigh, Charles C. Discussion on American Slavery: in Dr. Wardlow’s Chapel, between Mr. George Thompson and the Rev. R. J. Breckinridge, of Baltimore, United States, on the evenings of the 13th, 14th, 15th, 16th, and 17th June, 1836. Boston: I. Knapp, 1836.

Waugh, Barry, “Robert Jefferson Breckinridge (1800-1871).”

About the project

This page was created as part of an undergraduate research seminar taught in the Virginia Tech History Department by Professor Paul Quigley in Fall 2015. Follow the link to return to the course homepage: The Preston Family: Civil War Experiences.