By Cole Helms

- “The rebel army under Bragg, and the best officered and organized of any they ever had except perhaps the army of Lee around Richmond . . .” – John Henning Woods, Confederate conscript[1]

- “Thus, in every land, the most conspicuous monuments commemorate the great actors, not the great thinkers of the world’s history; and among these men of action the great soldier has always secured the first place in the affections of his countrymen.” – Archer Anderson at the Dedication of the Lee Monument in Richmond[2]

- “Many a general have I seen walk and a poor sick private riding his horse, and our father, Lee, was scarcely ever out of sight when there was danger.” – Louis Leon, Confederate soldier[3]

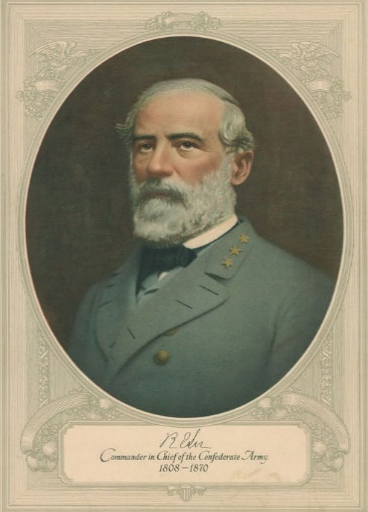

General Robert E. Lee undoubtedly had the support of most Confederates during the Civil War. In the southern states, the public relied on General Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia to boost their morale.[4] Lee also captured northerner’s attention during his campaign into the northern states. His accomplishments only boosted the confidence that his troops and fellow generals had in Lee, and it also helped to make sure northerners understood that Lee and his Confederates were dedicated to fighting for their independence from the Union.

Following 1865, General Lee was viewed as less of an enemy in the North than he had been during the war. In the South, his reputation was as a figurehead of the Lost Cause, along with the remaining generals and diplomats from the Confederacy (some of them pictured above with General Lee, front row, second from left). These men wanted their version of wartime events to be heard, and most white southerners were eager to listen to them.[5]

No “Scorched Earth” Policy

The compassion that General Lee showed his troops is one of the main reasons that he was so beloved by his own soldiers. General Lee’s offensive strategy drove him to breach northern borders and seek a showdown with the Union.[7]

Once within Union borders, Lee prohibited his men from pillaging or destroying villages as they passed through them. No houses were to be entered and no damage was to be done to properties. This was different from Union Major General William T. Sherman, whose name calls to mind images of fire and destruction, as well as Atlanta in flames later in the war. According to one Confederate soldier, northerners “rejoiced under the strict orders” of General Lee.[8] Some of Lee’s soldiers ignored those orders, however, taking property and committing cruel acts such as the kidnapping of free African Americans into slavery.

Military Accomplishments

Only after years of fighting did the North recognize Lee’s ability as a military commander.[9] During the Second Battle of Bull Run, General Lee embarrassed Union General Pope’s army by sending “Stonewall” Jackson’s wing into Pope’s rear and then hurled Longstreet’s wing into Pope’s exposed flank, leading to one of Lee’s greatest battles.[10] General Lee was able to give the Confederacy a chance even though he often had half the manpower of the Union.

At the Battle of Antietam, General Lee was again outnumbered on the battlefield with 45,000 Confederates opposed to General McClellan’s 87,000 Union men. Regardless, Lee was able to withhold the might of the Union, eventually ending in a draw between the two commanders. The Confederacy lost an estimated 10,316 soldiers that day but dealt a heavy blow to the Union by taking out an estimated 12,401 soldiers. Though he lost the battle–though he was severely outnumbered and outmatched, and though he retreated back into Virginia after the battle–Lee had shown his strength as a commander.

Relevance in Modern Times

Following the conclusion of the Civil War, various individuals and groups sought to erect monuments and sculptures of General Lee in order to preserve his memory. They erected numerous monuments as far north as The Bronx Community College in New York, New York and as far south as Dallas, Texas. Some Confederate statues and monuments have been removed in recent years and it appears that more shall fall behind them.

Perspectives on Lee have become much more divided in recent years. In August of 2017, the Lee Monument in Charlottesville became the latest statue to spark debate. Some residents hoped that it could be the next to be taken down. Protesters took matters into their own hands in some cities, tearing down the statues themselves, as happened in Durham, North Carolina.[11]

The root of the debate stems from the different memories that the statues represent in American’s minds. Proponents for the removal of the statues claim that they portray an overly positive vision of the slaveholding Confederacy’s past. Proponents of keeping the statues claim that by removing these symbols of our nation’s past, then the history of the South is effectively being removed as well. White supremacist groups are using the Confederacy and its symbols to bolster their belief that Caucasians should be in control, and that is what the Confederacy reminds them of.[12]

The debate that surrounds the removal of Confederate statues appears to have placed a target on General Lee’s granite back, as his statues have continuously come under attack in cities all over the United States. It seems that many years after the conclusion of the war, the reputation of General Lee has shifted into a more negative light. The controversy that surrounds General Lee and the statues that were erected in honor of him portray a shift in how Americans want to remember the Civil War and some of its most influential members.

Further Reading

Thomas, Emory. Robert E. Lee: A Biography. New York: W W Norton & Company, 1995.

Taylor, Walter. Four Years with Lee. Heraklion: Heraklion Press, 2013.

Leon, Louis. Diary of a Tar Heel Confederate Soldier. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Documenting the American South,1998.

Freeman, Douglas S. Lee. New York: Touchstone, 1997.

https://www.civilwar.org/learn/biographies/robert-e-lee

https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/3779/all-info

Jacey Fortin, “The Statue at the Center of Charlottesville’s Storm,” Aug. 13, 2017.

Footnotes

[1] John Henning Woods Memoir, Volume 3, Page 79. John Henning Woods Papers, Ms2017-030, Special Collections, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, Va.

[2] Archer Anderson, Robert Edward Lee: An Address Delivered at the Dedication of the Lee Monument (Richmond, Va: William Ellis Jones, 1890).

[3] Louis Leon, Diary of a Tar Heel Confederate Soldier, p. 41.

[4] Gary Gallagher, The Confederate War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, 1997), 8.

[5] Hahn, Steven. “Leader of the Lost Cause.” New York Times, Nov. 23, 2014. Accessed October 2017.

[7] Gabor Boritt, Jefferson Davis’ Generals (New York: Oxford University Press: 2000), 31.

[8] Leon, 33.

[9] Woods, Vol. 1, p. 41.

[10] Boritt, 37.

[11] Laura Anastasia, “Monumental Battle,” in Time Magazine. September 18, 2017. Accessed 4 December, 2017. Page 7.

[12] Anastasia, 8.

About the Project

This page was created as part of an undergraduate research seminar taught in the Virginia Tech History Department by Professor Paul Quigley in Fall 2017. Views and opinions belong to the student authors.

Return to The John Henning Woods Online Exhibit main page.