By Meghan McAuliff

In a time where most people were not literate, John Henning Woods was an exceptional writer. He was kind enough to lend his abilities to other men in the Confederate Army who wanted to write home to their wives, as he states on the twenty-second page of the second volume of his reflection journal, “In all the hundreds of letters I wrote to the “Dear Wives” I never penned a good word for the Confederacy, but her palpable wrongs I showed up in impressive style.” Woods was a Unionist that was drafted into the CSA army and did not have any kind words for the institution.

Woods’ mention of the hundreds of letters he helped other soldiers write home inspired my investigation of how effective correspondence was as a method of maintaining the nature of romantic relationships between men and women. At the time, marriages were paternalistic, meaning that men maintained an overarching protectorate and provisionary role in their families. In my research, I found that couples tended to maintain paternalism in spirit, but not in actuality due to the inherent limits of postal communication. This web version of my research contains only information about white elite women for the most part, with some consideration of women from other classes, but no consideration of women of other races for the sake of brevity.

Men and Women of the Civil War

Before the Civil War, the prevailing historic image of the archetypal Southern white woman and man were known as the “Southern Mistress” and “Southern Gentleman” respectively.[i] The Southern Mistress was firm in slave management, gentle, pure, and submissive to her husband, striving to serve him and her family. For men, masculinity was tied to generosity, sociability, pride, and honor.[ii] These ideal images of who a proper man or woman should be were not realistic for those of all classes but they still influenced how men and women viewed themselves. Further, the level to which a person could live up to these standards influenced how they were placed into society.

Committed Relationships in the 1860s

Back during the Civil War, the romantic relationships between men and women were paternalistic- women were placed under men’s protection and control. Elite white women, as a part of separate sphere ideology, lived in what was referred to as the “private sphere” where they were in charge of managing their home and often household slaves when applicable. Men, on the other hand, were in charge of the “public sphere” that largely encompassed business, farming, politics, and more. This role division created a mutual dependence within marital relationships- men and women were a team in which each member’s job was necessary for the perpetuation of the family’s lifestyle. Again, however, this was not a realistic separation for women of middling and lower classes because the complete domestication of women was not always economically viable as an option.

Surviving an Absence

When the Confederacy formed its army, men had to leave their homes and families behind to fight- whether they believed in the Confederate cause or not. With them gone, women were called to step into roles that were outside of their spheres and outside of their comfort zones. Without the ability to complete many trades or the skills required to produce food, families left on the home front often went without the resources they needed to live.

Women trying to collect debts so that they could buy much needed supplies were ignored when they didn’t have the correct documents- which were likely in their husband’s possession.[iii] Of course, had they been men, they would have been able to Further, they couldn’t rely on a response from their husbands because the post was so slow. Couples would complain that their letters had not gone through to the other, and miscommunications ran rampant.

Women were still receiving money when possible and promises of later help, but none of this could come close to the convenience of having an able bodied man at home to take care of public matters and to carryout the duties that the 1860s gender roles had made difficult for women.

Some situations became so desperate that women would rebel and act out in violence. The Richmond Bread Riots are a famous example of how women were forced to take drastic measures for the sake of self preservation when the traditional paternalistic institutions did not provide for them.

Love Conquers All- Until it Doesn’t.

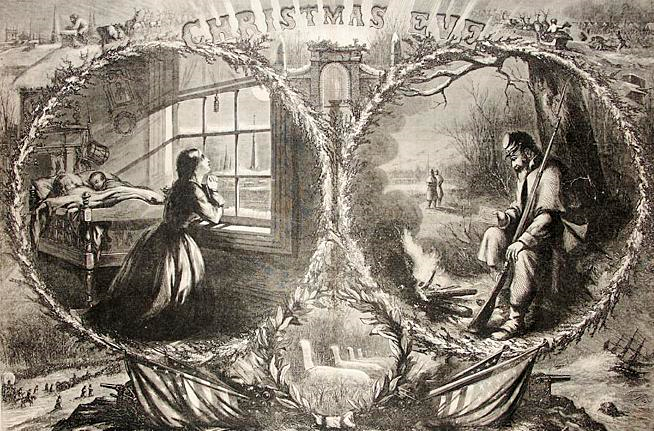

To communicate with each other, couples were forced to resort to writing letters. The process was slow and unreliable but, as one romantic correspondent so aptly put it, “This is an unpleasant mode of

conversing with each other, yet I feel thankful that we have this privilege.”[iv] Still, while they were able to keep up the bare bones of their relationships, men were unable to provide much needed advice and information to their wives trying to keep things together at home.

Still, as mentioned before, they did offer some assistance. Beyond that, they still gave their wives commands such as to stop using tobacco products or to avoid certain social behaviors. Further, and arguably more importantly, husbands and wives were able to express love to each other.

Thus, while the husbands weren’t able to provide the protection and provision that Civil War era society mandated of them, their wives still wanted them to. Most did not love their newfound place in the public sphere and they expressed very vividly that they wanted their husbands home, and their live to return to normal. As one woman stated, “We are starving. As soon as enough of us get together, we are going to the bakeries and each of us will take a loaf of bread. That is little enough for the government to give us after it has taken all our men.”[v] They wanted their men to return home- and soon.

This desire for paternalism fueled its return. When the Civil War was over and men returned to their marriages, things were certainly changed, but the same basic structure still reigned. All in all, paternalism, though not maintained physically during the war, was kept alive in the hearts of the men and women who participated.

Suggested Further Reading

If you’re curious about this topic or about women during the Civil War in general, you may want to read these great works by some of the most influential researchers in the field:

- “The Marriage of Varina Howell and Jefferson Davis” chapter by Carol Bleser

- Scarlett Doesn’t Live Here Anymore by Laura F. Edwards

- Mothers of Invention by Drew Faust

- Confederate Reckoning by Stephanie McCurry

- The Civil War Chronicle by Matthew Galman

Footnotes

[i] Stephanie Jones-Rogers, “Mistresses in the Making” Women’s America (New York, Oxford University Press, 2016), p. 216.

[ii] John Mayfield, Counterfeit Gentleman: Manhood and Humor in the Old South (Gainsville, Fl: University of Florida Press, 2009): 15.

[iii] Emily Beck Moxley to William M. Moxley, Pike Co., Alabama, 1 September 1861, in Oh, What A Lonesome Time I Had, (Tuscaloosa, Al: University of Alabama Press, 1861), 22-24.

[iv] Phoebe McCormick to Frank Heizer, 22 February 1865, Heizer Family Papers. Virginia Tech Special Collections, Virginia Polytechnic and State University.

[v] “Bread Riot in Richmond, 1863” as found in Matthew Galman, The Civil War Chronicle (New York: Konecky & Konecky, 2010).

About the Project

This page was created as part of an undergraduate research seminar taught in the Virginia Tech History Department by Professor Paul Quigley in Fall 2017. Views and opinions belong to the student authors.

Return to The John Henning Woods Online Exhibit main page.