By Rachel Snyder

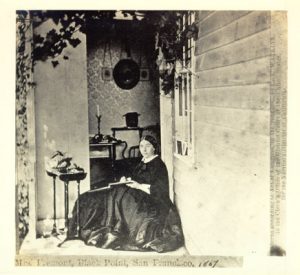

- Born Jessie Ann Benton on May 31, 1824 to Missouri senator Thomas Hart Benton and Elizabeth Preston McDowell.

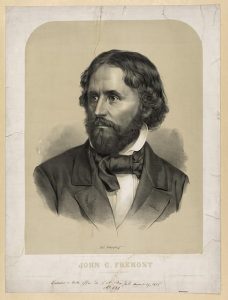

- Eloped with John Charles Frémont, the “Pathfinder,” October 19, 1841.

- Broke from her Democratic father to support her Republican husband’s 1856 presidential campaign.

- In 1861, visited President Abraham Lincoln in Washington D.C. to defend her husband’s decision to proclaim emancipation in Missouri.

During the nineteenth century, there were two idealized spheres: Public and private. Men dominated the public sphere of business and politics while women remained confined to the private sphere of home and family, only venturing into the public sphere through moral reform societies.

Then there was Jessie. The wife of the adventurer and army officer John Charles Frémont and the daughter of a Missouri senator, Jessie Benton Frémont defied nineteenth-century gender norms. By involving herself in her husband’s political career, she pursued her own political ambitions, shocking some, impressing others, but ultimately creating a reputation as a stateswoman.

“Impressed all who came in contact with her by her great intellectual powers”

Politics played an important role early on in Jessie’s life. As the second daughter of Missouri senator Thomas Hart Benton, Jessie came in contact with people of all walks of life who came to do business with her father. Visitors included General William Clark, heads of the American Fur Company, prominent author Washington Irving, Mexican merchants, soldiers fighting Native Americans on the frontier, Italian and Belgian dignitaries, French voyageurs, and wealthy French, Spanish, and American citizens.[1] Benton also gave his daughter an extensive education. As a result, when Jessie publically entered politics, contemporaries observed she “Inherit[ed] her father’s talent and many salient points of his character,” and “impressed all who came in contact with her by her great intellectual power.”[2] Thus, Jessie’s father offered the first steps into the political arena.

“I would as soon place my children in the midst of smallpox”

Her mother also influenced her political views. Elizabeth Preston McDowell came from the influential Preston family of Virginia. While she epitomized the ideal nineteenth century wife and mother, she did involve herself in the slavery issue. In a letter to writer and abolitionist Lydia Maria Child, Jessie credited her own anti-slavery stance to her mother and claimed, “I would as soon place my children in the midst of smallpox, as rear them under the influence of slavery.”[3]

Jessie’s entrance into politics grew gradually after her marriage to John Charles Frémont. Frémont already had a reputation as an adventurer when he met Benton through their shared interest in Westward Expansion. Jessie expanded Frémont’s reputation by documenting and publishing his adventures from his 1842, 1843, 1845, 1848 and 1853 expeditions to map the West and find a year round land route to California.

Jessie’s greatest political intervention occurred during Frémont’s second expedition in 1843 when she detained an order from Frémont’s commander in the U.S. Army’s Bureau of Topographical Engineers recalling him to Washington. Seeing in it a scheme by opposing forces in Washington to prevent the expedition, Jessie acted to shield the mission and thus her husband’s career.[4] Jessie made her own executive decision based on her political convictions.

However, it was not until her husband’s 1856 Republican presidential campaign that Jessie came into her own. Founded in 1854 on an anti-slavery platform, the Republican Party grew quickly, gaining enough support by 1856 that its members felt confident enough to put up a candidate in the presidential election. Despite Jessie’s father being a Democrat, Frémont accepted the Republican Party’s offer to be its presidential candidate.

“Our Jessie!”

Jessie’s role in the campaign included protecting her husband from the opposition’s attacks and garnering public support. During the campaign newspapers observed, “Beautiful, graceful, intellectual and enthusiastic, she will make more proselytes to the Rocky Mountain platform in fifteen minutes, than fifty stump orators can win over in a month.”[5] Calls for “Our Jessie,” “Let us see Jessie,” and “We want both the Colonel and his Jessie,” permeated through the crowds that followed Jessie and Frémont along the campaign trail.

“She is a woman as eminently fitted to adorn the White House”

Jessie’s involvement in the campaign demonstrated her abilities as a stateswoman and led supporters to call for her placement in the White House. The Boston Daily Atlas claimed, “If the gallantry of the country demanded a Queen at the head of the nation, the lovely lady of the Republican nominee would command the universal suffrage of the people. She is a woman as eminently fitted to adorn the White House, as she has proved herself worthy to be a hero’s bride.”[6] Jessie embodied the qualities that the public associated with politicians.

Jessie’s career in politics continued after her husband’s defeat in the presidential election by Democrat James Buchanan. At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, President Lincoln made Frémont head of the Western Department. In July 1861 the Frémonts moved into the headquarters of the Western Department in St. Louis. As inhabitants of a slave state that stayed in the Union, Missourians’ loyalties were split. Plagued by guerilla warfare, open recruitment by the Confederates, mismanagement, and limited supplies and troops, Frémont got to work pushing the rebels back while Jessie ran headquarters and tried to get Frémont the supplies he needed.

“General Jessie”

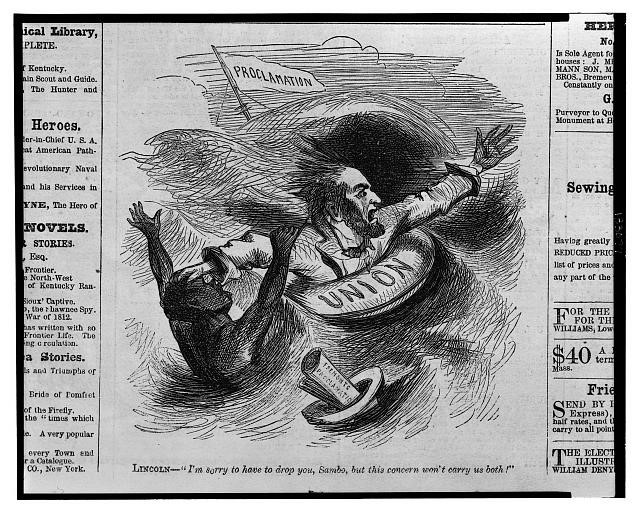

However, it was not long before Frémont’s leadership came into question, with cries of corruption and mismanagement, and Jessie’s involvement came under scrutiny. Dubbed “General Jessie” by critics, Frémont’s opponents attributed his inability to efficiently run his department to her talent and energy.[7] Jessie did not let these criticisms stop her from following her political agenda. On August 31, 1861, after only consulting his wife and the Quaker abolitionist Edward M. Davis, General Frémont, without Lincoln’s authorization, issued a proclamation declaring martial law in Missouri.

The proclamation placed Jessie in the middle of a great scandal. The proclamation freed all slaves held by rebels, confiscated all rebel owned property and tried all those carrying arms by court martial.[8] Lincoln feared the proclamation would alienate the Border States, and wrote Frémont asking him to change the paragraph in the proclamation related to emancipation.

Alongside the backlash over the proclamation, Colonel Frank P. Blair, brother of Post-Master General Montgomery Blair and long time Benton family friend, wrote a letter to his brother describing the “rascality going on here under Fremont’s sanction and even direction.”[9] The letter found its way to the President, who sent Post-Master General Blair and Quarter-Master General Meigs to Missouri to investigate the affair. With his administration in shambles and refusing to change his proclamation, Frémont sent Jessie to Washington to defend his case in front of the president.

“Quite a female president”

It was here that Jessie’s abilities as a stateswoman shined. Even President Lincoln commented that she was “quite a female politician.”[10] Newspapers described her as “envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary.”[11] Despite her efforts, on November 3, 1861 Lincoln relieved Frémont of his command of the Western Department.

For the rest of the Civil War, Jessie’s involvement in politics took on a different form. She attempted to salvage her husband’s reputation by publishing The Story of the Guard. The book described the exploits of Frémont’s personal bodyguard who served him during his command of the Western Department. The book allowed Frémont to tell his version of his days as commander of the Western Department.

Furthermore, Jessie became increasingly involved in the Sanitary Commission. Jessie took a particularly active role in the organization of the Sanitary Commission’s Fair in 1864. Despite opposing political views, Jessie worked alongside Mary Ellen McClellan, wife of the disposed general and Democratic presidential candidate, on the Arms and Trophies committee. Jessie also headed a committee to collect and publish the memoirs of sanitary commission workers.

Throughout Jessie’s life, she remained in contact with influential abolitionists, women’s rights advocates, and influential politicians. Jessie spent the rest of her life traveling with her husband and writing about her experiences. She passed away in 1902 at her home in Los Angles, California, remembered by the public as the influential stateswoman she was.

Notes

[1] Jessie Benton Fremont, “The Origin of the Fremont Explorations,” Century Illustrated Magazine 41 (Mar. 1891): 767.

[2] “Fremont and the Blairs, ” San Francisco Bulletin, Oct. 5, 1861.

[3] To Lydia Maria Child from Jessie Benton Frémont, Jul./Aug. 1856, in The Letters of Jessie Benton Frémont, ed. Pamela Herr and Mary Lee Spence (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 122.

[4] “Our Jessie,” The Age (Augusta, Maine), Aug. 7, 1856.

[5] “Give Em’ Jessie,” Boston Daily Atlas, June 27, 1856.

[6] “Give Em’ Jessie,” Boston Daily Atlas, June 27, 1856.

[7] Pamela Herr and Mary Lee Spence, eds., The Letters of Jessie Benton Frémont (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 244.

[8] Ibid., 246.

[9] “Fremont and the Blairs,” San Francisco Bulletin, Oct. 5, 1861.

[10] Frémont, “Great Events,” in The Letters of Jessie Benton Frémont, 265-266.

[11] “Fremont and the Blairs,” San Francisco Bulletin, Oct. 5, 1861.

Further Reading

Herr, Pamela and Mary Lee Spence, eds. The Letters of Jessie Benton Frémont. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

Thomas Smith, Michael. “Corruption European Style: The 1861 Frémont Scandal and Popular Fears in the Civil War North.” American Nineteenth Century History 10 (March 2009): 49-69.

Stone, Ilene and Suzanna M. Grenz. Jessie Benton Frémont: Missouri Trailblazer. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2005.

Volpe, Vernon L. “The Frémonts and Emancipation in Missouri.” The Historian 56 (Winter 1994): 339-354.

Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. “Notable Visitors: Jessie Benton Frémont (1824-1902).” Mr. Lincoln’s White House. http://www.mrlincolnswhitehouse.org/inside.asp?ID=714&subjectID=2.

About the project

This page was created as part of an undergraduate research seminar taught in the Virginia Tech History Department by Professor Paul Quigley in Fall 2015. Follow the link to return to the course homepage: The Preston Family: Civil War Experiences.