By Michael M. Higgins

- Born November 8 1813 in Montgomery County, Virginia to a prominent slaveholding family.

- After a brief tour as a soldier and a successful career as a lawyer, Preston joined the Confederate Army following Virginia’s secession.

- Was close to General “Stonewall” Jackson and was likely the first soldier to holler the ‘Rebel Yell,’ impacting southern culture for decades.

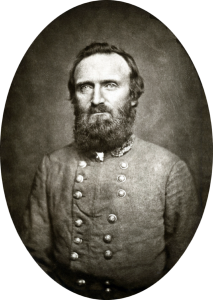

The Rebel Yell is a hallmark of Southern Culture. It has permeated American contemporary culture: from a brand of whiskey, to the lyrics of songs by Billy Idol and Eminem, to the name of a roller coaster. The Rebel Yell is one of the few legacies of the extinct Southern Confederacy that the wider populace of the United States today seems to accept without question. Though General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson was the first officer known to give the order to “yell like furies,” it was probably Colonel James Preston who actually took up the call.

Early Life

James Francis Preston was born on November 8 1813 at Smithfield,1 his family’s home in Montgomery County, Virginia. His father, James Patton Preston (1774 – 1843) was a wealthy plantation owner, a colonel in the United States Army during the War of 1812, and the Governor of Virginia from 1816 to 1819. His Grandfather was William Preston (1729 – 1783), the founder of Smithfield Plantation, a signer of the Fincastle Resolutions, and a Colonel in the Revolutionary War. James F. Preston studied first at Washington College2 (Now Washington and Lee) and then at the United States Military Academy at West Point in the early 1830s before returning to Montgomery County to start his own law practice.

In 1846, following in the military traditions of his father and grandfather, James Preston was commissioned a Captain in the 1st Regiment of Virginia Volunteers at the outset of the Mexican-American War. He served in Mexico from January 16th, 1847 to July 31st, 1848.3 He resumed his law practice upon returning home.

The Prestons had a family tradition of going into politics. In addition to his father and grandfather, his brother, William Ballard Preston, was a US Representative and soon to be Secretary of the Navy who was known for supporting gradual abolition. James F. Preston endeavored to follow his family members in their illustrious careers. In 1852 he was elected the Montgomery County Representative to the Virginia House of Delegates. He was not re-elected.4 James F. Preston returned to Montgomery County in 1853 and in 1855 married Sarah Ann Caperton and built his plantation, “Whitethorn.”5 James Preston had, during this period, acquired 19 slaves from his father’s estate, courtesy of his brother William, who was still professing gradual abolitionism. He lived on Whitethorn quietly for a few years, continuing his law practice and raising his three sons.

Civil War: First Battle of Manassas

James F. Preston’s second career as a soldier began with his commission into the Virginia Militia, and subsequent transfer to the Confederate Army, on April 24 1861. James Preston left no memoir or letters regarding his feelings toward secession. One can assume, however, that there was typically more than one reason for a man to revoke his allegiance to his nation as a whole and follow his state. Preston had economic reasons as a slaveowner to have a vested interest in the continuation of that ‘peculiar institution.’ He also had a brother (William Ballard Preston) who would become a Senator in the new Confederate Congress and standing in the community that would have expected him to go to war. Or it could have just been, as a future subordinate James McMurran put it: “Noble State pride and love of home.”6 Most likely it was a combination of the three.

James F. Preston was promoted to colonel in the Confederate army and became the commanding officer of the 4th Virginia Infantry. He and the men under his command received some of the most intense and rigorous training by any group of Confederate soldiers during the early summer months while stationed at Harper’s Ferry, northwest of the Union capital: Washington D.C.7 This was thanks to Colonel Preston’s new and untested Brigade commander: Thomas Jackson, whom posterity would refer to as “Stonewall.”

Mary Caperton, who was James F. Preston’s sister-in-law, was living with Sarah Ann Preston at Whitethorn during these months and wrote several letters to her husband describing the movements and location of Colonel Preston.

On the morning of July 18 1861, Colonel Preston Received orders to march to Manassas Junction. After a day’s march to Winchester, Virginia at around 8 a.m. on Friday July 19 Col. Preston ordered the 4th Virginia Infantry to climb into railroad cars to take them to the battle more quickly. He wouldn’t know it, but Col. Preston had for the first time in history ordered the largescale movement of soldiers by railroad.8 The 4th Virginia arrived on the field of Manassas before dawn on July 21st, 1861.

Colonel James Preston wrote his wife a letter describing in detail what occurred on the battlefield. After lying on the ground for over two hours, just behind the crest of a hill where the Confederate cannons were placed. Col. Preston described how more than 20 soldiers were wounded and that the actual fighting portion of the battle was not as bad as the pounding they took on the hill. When General Jackson ordered the 4th Virginia to charge the Colonel relates:

“General Jackson gave me the order to up and charge the enemy who were advancing on our left flank. The regiment rose with promptness and charged (them) with a cheer that resounded far and near”9

As the commanding officer of the 4th Virginia, Colonel James Preston would have been the officer leading not only the charge, but the yell, making him likely the first man to utter the ‘Rebel Yell.’ The 4th Virginia went on to capture the Union artillery under Sherman and drive back a three different Union pushes to retake them.10 Up until this point the Union had been winning the battle, but the Confederates rallied around the 4th Virginia’s charge and ended beating back the Union troops until they were in a full scale unorganized retreat back to Washington D.C. The 4th Virginia, under Col. Preston and Gen. Jackson, had won the day for the Confederates, and had given the rebels something to rally around and form into an identity: the Rebel Yell.

The end of the battle was not as flawless as some of the Confederate commanders would have liked however. The Confederate army was in just as disarray in victory, and they had suffered more casualties.11

Civil War: Camp Life

James F. Preston wrote a letter one month after the battle of Manassas which describes the monotony of camp life during the conflict. He says that there were rumors that the Union Army had taken Fairfax, but after two separate forced marches this was proven to be false.12 He speaks of other rumors as well about what the enemy are doing. Preston mentions that over thirty men of Company I are sick. That is 30%. Among the sick is the regimental chaplain. Preston sums up camp life with the curt sentence:

“You will suppose that a soldier requires patience and perseverance as well as courage.”13

Death and Legacy

After several months of tending to his wound in the army, including a brief two-week command as a brigade commander, he was forced to quit his commission and return home to Whitethorn. James Francis Preston would not live to see the end of the war. He died of complications to Rheumatism on January 20th, 1862.14 He was only 49. 1862 was a depressing year for the Prestons as they lost Col. James Preston, his son James F. Preston Jr. to Typhoid fever, and his brother Sen. William B. Preston. In the end the Prestons could not save their society, their way of life, or even their own lives. But James Francis Preston never set out to accomplish all that on his own. He was simple man that fought to defend his home, but he left us a deafening legacy. He would never know how far afield his lungs would carry his scream.

Further Reading

Dorman, John. The Prestons of Smithfield and Greenfield in Virginia. Louisville: TheFilson Club Incorporated, 1982.

Preston Family Correspondence, 1861, 1872 Special Collections, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Caperton Family Papers, 1861-1862. Special Collections, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

James F. Preston Correspondence. Library of Virginia. Accession #41577.

Hennessy, John. The First Battle of Manassas: An End to Innocence July 18-21, 1861. Lynchburg: H.E. Howard, Inc., 1989.

Robertson Jr., James I. 4th Virginia Infantry, 2nd ed. Lynchburg: H.E. Howard, Inc., 1982.

Robertson Jr., James I. Stonewall Jackson: The Man, The Soldier, The Legend. New York: MacMillan Publishing USA, 1997.

References

- John Dorman, The Prestons of Smithfield and Greenfield in Virginia. (Louisville: The Filson Club Incorporated, 1982), 266.

- James P. Preston to James McDowell, September 12, 1831. Letter. From Special Collections, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Smithfield Preston Foundation Papers.

- Dorman, 266.

- Ibid, 266.

- “Virginia Department of Historic Resources.” accessed November 14, 2015, http://www.dhr.virginia.gov/registers/Counties/Montgomery/150-5021_Whitethorn_1989_Final_Nomination.pdf

- James I Robertson Jr., 4th Virginia Infantry, 2nd ed. (Lynchburg: H.E. Howard, Inc., 1982), 1.

- Mary E. Caperton to George H. Caperton, June 4, 1861. Letter. From Special Collections, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Caperton Family Papers, 1861-1862.

- V.C. Jones, First Manassas: The Bull Run Campaign. (Harrisonburg: Eastern Acorn Press, 1980), 19.

- James F. Preston to Sarah Preston, July 28, 1862. Letter. From Special Collections, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Preston Family Correspondence, 1861, 1872.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- James F. Preston to Charles, August 28, 1861. Letter. From Library of Virginia.

- Ibid.

- Emily Allen, and Devota P. Pack, comp. Deaths in Court of Montgomery County, Virginia 1853-1871. (N.p., 1977), 19.

About the project

This page was created as part of an undergraduate research seminar taught in the Virginia Tech History Department by Professor Paul Quigley in Fall 2015. Follow the link to return to the course homepage: The Preston Family: Civil War Experiences.