By Colin Stamper

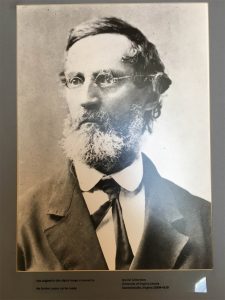

- Born in British Guiana to Joseph H. Holmes and Mary Ann Pemberton on August 21, 1820.

- Author of articles in various southern publications including De Bow’s Review, Southern Quarterly Review, and Southern Literary Messenger.

- Professor at several institutions including University of Mississippi and University of Virginia where he taught subjects like history, foreign languages, and political economy.

- Generated numerous connections with high-ranking officials throughout the South who contacted him for political assistance during the Civil War era.

University of Virginia).

The crisis of the Civil War demanded the involvement of Americans from all walks of life. Politicians rose to prominence and military men fought on the battlegrounds. A lesser known group, the intellectuals, were fighting the war on a different front, through scholarly work and education. These intellectuals used their authority as the experts in their respective fields to create a national identity in the South and help the Confederate war effort. George Frederick Holmes was just one of the many intellectuals who worked in both of these fields and used his influence as a scholar to broadcast his ideas on controversial subjects such as slavery throughout the Confederate South and beyond.

The Life of a Scholar

Born in British Guinea and raised and educated in Durham, England, Holmes had a vastly different early life than many other supporters of the Confederacy. He was held to high expectations as a child and excelled in primary school. He went on to the University of Durham but left after one year in 1837 to travel to North America.

Soon after his arrival in the United States he traveled to South Carolina to pursue a law career. There he met and practiced under Colonel William Preston for several years. Soon after, Preston introduced Holmes to his granddaughter Eliza Floyd, a descendant of the prominent Preston family and daughter of John Floyd the Governor of Virginia. The two were married in 1845 and had seven children together, only five of whom made it into adulthood. Several years before their marriage, Holmes left his profession as a lawyer and became a writer and an educator until his death in November of 1897.

Scholarly Work and Academic Articles

Most of Holmes notable work is found within his contributions to southern periodicals such as De Bow’s Review and Southern Literary Messenger. Although Holmes had a deep love of writing his earnings were low. Between 1839 and 1861 Holmes published 111 different articles but averaged nearly one dollar a page, which crippled him and his family financially.[1]

In these articles Holmes wrote about various subjects including the controversial topics of slavery and North-South differences. These articles created tensions between northern and southern intellectuals and the South started to not only attack the North physically but intellectually. Historian Michael Bernath speaks about this topic in his book Confederate Minds stating, “During the first year of the war, southern writers spent as much time attacking northern culture and decrying the pernicious influences of northern literature and education as they devoted to erecting an alternative southern culture.”[2] By discrediting the North the Southerners could assert their perceived superiority and attract attention to their cause and home and abroad.

Further, Holmes became a spokesman for the pro-slavery cause in the South. Many of his writings in southern publications featured reviews of scholarly work regarding the highly debated institution of slavery. One of his notable articles is a review of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Toms Cabin, which he published in the Southern Literary Messenger in 1852. In this review he asserts that the work is fiction and personally attacks Stowe stating, “With the hope of expediting or achieving the attainment of the fanatical, and in great measure, merely speculative idea of substituting the real thralldom of free labor for the imaginary hardships of slavery.”[3]

In contrast, Holmes commends his associate Albert Bledsoe for his work “On Liberty and Slavery” by affirming his integrity and reiterating the accuracy of his facts.[4] Holmes used his authority as an academic to write these reviews and convey the important points of these works to assert his own views and influence on slavery.

Contributions to Education

While Holmes was penning these articles he also pursued his other interest, education. Holmes held positions at several prominent Universities throughout the South including William and Mary, University of Mississippi, and University of Virginia, where he taught for 40 years. During his time at these universities he became immersed in southern culture and made connections with important people of the South.

But the college campuses were not immune to the effects of the Civil War. While they were not the epicenter they offered a unique opportunity for students to voice their opinions. Historian Michael Cohen notes in his book Reconstructing the Campus that “a college brought youths together and encourages them to analyze and debate important questions; the hothouse atmosphere of a college during a national crisis thus made youths passionate and sometime radical in their sectional views.”[5] This is very revealing of Holmes years as an educator and the environment of college campuses during the Civil War.

Apart from lecturing students at these Universities and writing articles, Holmes dedicated his free time to writing textbooks for school students. One of his most significant texts was his A School History of the United States, which was originally published in 1877 and gave a brief history of the United States with emphasis on the Civil War years. General Robert E. Lee commissioned this textbook to Holmes in a letter where he wrote, “I feel more strongly than I can describe the importance of a true history of the war between the Northern and Southern States, and had resolved to prepare a narrative of the military occurrences in Virginia.”[6] This letter from the famed General displays Holmes connections to high-ranking officers in the Confederacy but also gave him and opportunity to write and influences his readers on his viewpoints of the war and its purpose.

Political Influence

Through Holmes work in the areas of scholarly work and higher education, he was able to network with important people throughout the South. Paired with his knowledge of subjects in areas such as politics and foreign languages, Holmes became a confidant and a resource to the Confederate government and its prominent officials. Holmes displays his understanding of the state of the nation is a series of letters sent to his brother where he talks about the war and its effects throughout the divided nation.[7]

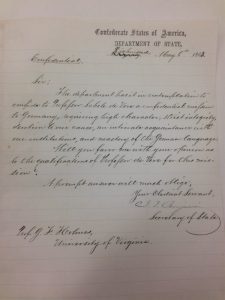

Additionally, his connections with the Confederate government are affirmed in a letter he received from the Department of State (pictured). The letter asks for Holmes’ opinion and recommendation of a colleague for a confidential mission to Germany.[8] This letter shows how southern intellectuals were useful to the Confederate war effort and how their influence permeated into the governmental affairs of the Confederacy.

Historical Significance of the Southern Intellectual

While George Frederick Holmes was just one of many southern intellectuals, his life story and work are very telling of the authority and influence that these academics had during the Civil War era. These intellectuals used their position in society, as experts in their respective fields, to exert their authority through their scholarly work. While they may seem withdrawn from the crisis of the time, they used their ability to influence others to rise in the ranks of literature, higher education, and politics while leaving an everlasting mark on the trials of the Civil War era.

Notes

[1] Michael O’Brien, Conjectures of Order: Intellectual Life and the American South, 1810-1860 V1, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 549.

[2] Michael T. Bernath, Confederate Minds: The Struggle for Intellectual Independence in the Civil War South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 35.

[3] George Frederick Holmes, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin Review,” Southern Literary Messenger, (1852): 723, http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/reviews/rere24bt.html.

[4] George Frederick Holmes. “Bledsoe on Liberty and Slavery,” De Bow’s Review 21, no. 2 (1856): 142, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/moajrnl/acg1336.1-21.002/146.

[5] Michael Cohen, Reconstructing the Campus: Higher Education and the American Civil War (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012), 25,58,37.

[6] Robert E. Lee to George Frederick Holmes, July 11, 1869, George Frederick Holmes, preface to A School History of the United States, (New York: University Publishing Company, 1877), 3.

[7] George Frederick Holmes to Edward A. Holmes, in George Frederick Holmes Letters, 1854-1886, Accession #14748-a, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

[8] Letter from Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin to Holmes, May 6, 1863, George Frederick Holmes Papers, Library of Congress.

Further Reading

Holmes, George Blake. Life and Contributions of George Frederick Holmes, Scholar, Teacher, and Writer (1820-1897). Special Collections, University Libraries, Virginia Polytechnic and State University, 1957.

O’Brien, Michael. Conjectures of Order: Intellectual Life and the American South, 1810-1860 Volume One. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

George Frederick Holmes Letters, 1854-1886. Accession #14748-a. Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, VA.

About the project

This page was created as part of an undergraduate research seminar taught in the Virginia Tech History Department by Professor Paul Quigley in Fall 2015. Follow the link to return to the course homepage: The Preston Family: Civil War Experiences.