By Courtney Ebersohl

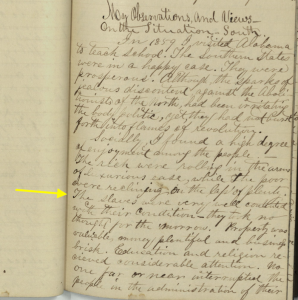

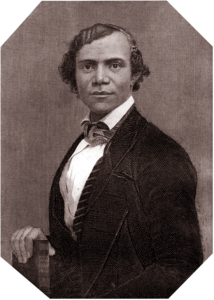

John Henning Woods, like many white southerners, believed in the inferiority of African Americans, through the mistaken assumption that enslaved people* “were contented with their condition.” Have human beings ever happily accepted the status of property? How did enslaved people challenge the institution of slavery and white society?

Through religion, enslaved people resisted slavery. Religious life in the enslaved community served as a defense against slavery and a source of collective strength. Religion offered a social sphere within enslaved communities that relieved experiences of dehumanization under slavery.

Secret Religious Meetings

Many enslavers required African Americans to attend church with white people and white preachers so that they could control their access to religion. In order to experience more authentic preaching, African Americans formed their own “invisible institution” in the slave quarters (Raboteau, Slave Religion). While white people were not watching them, enslaved people preached and discussed their own interpretations of the bible during secret services and meetings. According to Marry Gladdy, a former enslaved person in Georgia,

“it was customary among slaves during the Civil War period to secretly gather in their cabins two or three nights each week and hold prayer and experience meetings.”

During these meetings, Gladdy explained how they talked with each other about their experiences, shook hands, and chanted canticles together. Through these acts, the people on Gladdy’s plantation fostered a community.

Wash Wilson, a former enslaved person from Texas, described how the enslaved people on his plantation would sing “Steal Away to Jesus” during the day to indicate that a religious meeting would occur that night. He explained that enslavers did not approve of religious meetings and that the enslaved people on his plantation would “slips off at night, down in de bottoms or somewhere. Sometimes us sing and pray all night.” Religion offered an identity that was not based on the condition of their slavery.

Continuation of Prayer

On plantations where enslavers forbad all forms of religion, including the white interpretation of the bible, acts of religious expression like prayers were especially dangerous. Celestia Avery evoked in a narrative in American Slave the story of her grandmother who liked to pray on a plantation run by an enslaver who forbid prayer. He beat her every day, yet she continued to practice her religion despite the consequences of terror and violence.

Black Church Services

According to Eugene Genovese, a historian of American slavery, enslaved people preferred the Baptist and Methodist churches because these two interpretations of Christianity had a fiery style and uninhibited emotionalism. African Americans developed their own patterns of religious expression within these churches in order to circumnavigate rules and include West African traditions. Methodists did not allow dancing because they believed it to be sinful behavior. Instead of dancing, enslaved people began “shouting.”

Video: Georgia Geechee Gullah Ring shouters’ performance in Riceboro, Georgia on March 11, 2011.

As the ring shouters demonstrate in this video, two or three people would clap their hands and tap their feet to a rhythm while other participants would walk single file around in a ring while singing spirituals, ensuring that they did not cross their feet. If they did not cross their feet, they were not dancing. They shuffled around the circle in a slightly stooped position and combined movements that incorporated the entire body. This style of dancing reflected the West African belief that bended joints were indicative of energy and life (for more information on African influences on American dance forms click here).

Spirituals

Spirituals allowed enslaved people to combine African traditions with Christianity. Spirituals were not only sung, but also performed in the ring shout where a leader called out a verse while the shouters responded by walking around the circle. James L. Smith, a former enslaved preacher in Virginia, described spirituals:

“The singing was accompanied by a certain ecstasy of motion, clapping of hands, tossing of heads, which would continue without cessation about half an hour; one would lead off in a kind of recitative style, others joining in the chorus.”

Participating in these spirituals allowed for enslaved people to relieve stress and manage their grief by sharing experiences that inspired intrapersonal and interpersonal hope. Enslaved people reflected the hardships of slavery through spirituals that they not only performed, but also spontaneously created. A former enslaved person described the process:

I’ll tell you; it’s dis way. My master call me up and order me a short peck of corn and a hundred lash. My friends see it and is sorry for me. When dey come to de praise meetin’ dat night dey sing about it. Some’s very good singers and know how; and dey work it in you know; till dey git it right; and dat’s de way.

This style of composition offered emotional support to members of the group and fostered empathy between people who shared common experiences.

Preference for Black Services

Enslaved people preferred black preachers who often preached a message of spiritual equality between white people and people of color.

Anthony Dawson, enslaved in North Carolina, recalled the difference between black and white preachers by emphasizing that “mostly we had white preachers, but when we had a black preacher, that was Heaven.” Dawson, like many other enslaved Christians, preferred black preachers because they believed that they had more authentic messages.

Litt Young, enslaved in Mississippi, explained that his enslaver told the preacher to tell the other enslaved people to “obey our master and missy if we want to go to Heaven, but when she wasn’t there, he come out with straight preachin’ from the Bible.” Young believed that the more pious sermons were the ones not influenced by white people. He believed those services were corrupted and insinuated that one did not have to obey an enslaver in order to obtain salvation.

Marriage

Even though slave marriages were never recognized by law, many enslaved people regarded marriage as a permanent commitment valued through their religious beliefs. Sometimes enslavers would arrange and force marriages. However, for many enslaved people, marriage offered an opportunity to make decisions that their enslavers could not make for them.

Henry Bibb married a woman named Melinda from a neighboring plantation, and recalled that “notwithstanding our marriage was without license or sanction of law, we believed it to be honorable before God.” They believed in their partnership and did not need white society to dictate their identity to them. Marriage offered an identity not based on an enslaved person’s status.

Collective Identity and Pride

For the average enslaved person, religion offered comforts that the institution of slavery denied them. Slavery attempted to strip people of their humanity, as they were only valued for their labor and bodies. Religion comforted people and gave them a semblance of autonomy. Even though enslaved people did not intend to revolt, their preferences for black preachers, their development of identities, socialization, and emotional releases opposed the objectives of slavery. These human experiences and decisions challenged an enslaver’s goal of dehumanizing African Americans. Enslaved people may have made decisions with the purpose of surviving a system that valued them as tools and machinery, but the consequences of their actions challenged the objectives of the institution to which they were confined.

*A Note on Language: Enslaved Person Vs. Slave

You may have noticed that I use the words “enslaved person” instead of “slave.” I prefer using an adjective to describe the people who were subjected to slavery because “person” or “people” makes us perceive them as individuals and as people instead of describing them by their position in society. Enslaved people were much more than their status as property. “Enslaved” also holds enslavers and people who supported the institution of slavery accountable for their actions. It reminds us of the condition in which these people lived.

Further Reading

During the Great Depression, the US government employed writers as part of the Works Progress Administration. They recorded the lives of over 2,300 former enslaved people from seventeen states. The Library of Congress digitized these first-person accounts of slavery and 500 black-and-white photographs of former enslaved people.

Blassingame, John W. Slave Testimony: Two Centuries of Letters, Speeches, Interviews, and

Autobiographies. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1977.

Genovese, Eugene D. Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made. New York: Vintage

Books, 1976.

Raboteau, Albert J. Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South. New

York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

About the Project

This page was created as part of an undergraduate research seminar taught in the Virginia Tech History Department by Professor Paul Quigley in Fall 2017. Views and opinions belong to the student authors.

Return to The John Henning Woods Online Exhibit main page.