By Emily Oliver and Courtney Penzo

- Born in Milton, Pennsylvania in 1820 to Julia Rush Miller and George Junkin, a Presbyterian minister.

- In 1857 she married Major John Thomas Lewis Preston, grandson of William and Susanna Preston.

- Became known as the Poetess of the South through her many poems supporting the Confederacy.

Education: The Birth of a Poet

Margaret Junkin was born in 1820 in Milton, Pennsylvania to Julia and George Preston. Her father, a Presbyterian minister and a professor, administrator, and president of various Presbyterian universities, was the most influential person in her young life due to the way in which he invested in Margaret’s education.[1]

George Junkin immediately recognized the intellectual potential in his young daughter and cultivated it with a rigorous education. He began teaching her Greek and Latin when she just six-years-old and provided her with excellent tutors and mentors throughout her youth. With this foundation, Margaret went on to complete all of the coursework necessary for a degree while living in the intellectual communities of Lafayette College and Miami University of Ohio.[2]

Margaret also began writing and publishing her own poetry during this period. She wrote Romanic style verse that that treated themes such as family, religion, nature, classical literature, and tales of the Revolutionary War. Immediately, her peers recognized her talent. One of her contemporaries from her days at Lafayette College, Reverend T. C. Porter, remembers, “Her remarkable poetical talent had even then won the admiration of her associates, and to have been admitted into the charmed circle of which she was the centre [sic], where literature and literary work were discussed, admired, and appreciated, I have ever counted a high privilege.”[3]

Marriage: A Pivotal Change

In 1848, Margaret Junkin moved to Lexington, Virginia with her family when her father accepted the presidency of Washington College.[4] This move represents a critical turning point in Margaret’s life. The defining events in Margaret’s life, and more particularly her literary career—her marriage to John Thomas Lewis Preston and her conversion to an ardent Confederate—are dependent upon her relocation to Lexington.

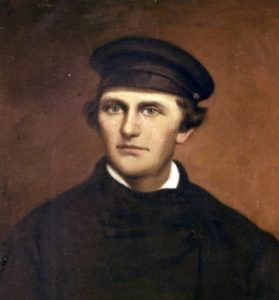

Margaret married John Thomas Lewis Preston (J.T.L.), founder of the Virginia Military Institute, in 1857. The pair had an intriguing relationship from the beginning. Margaret was 35, almost twice the age of the average southern bride, when she married J.T.L. He on the other hand was nine years her senior, a widow, and the father of seven children.[4] This relationship, which ultimately became the most important relationship in defining Margaret’s Civil War loyalties and the course of her literary career, presented many challenges and difficult choices early on.

As a new wife, Margaret was overwhelmed by all of her responsibilities. These included caring for her seven new stepchildren, maintaining the house and plantation, and entertaining frequent visitors. She also gave birth to two sons of her own, George Junkin Preston in 1858 and Herbert Rush Preston in 1861.[5]

The onset of the Civil War presented another challenge in Margaret’s marriage to J.T.L. Due to his Northern roots, Margaret’s father George Junkin remained staunchly loyal to the Union throughout the war and even moved back to Pennsylvania in 1861. Her husband on the other hand, served in the Confederate military and was very open about his loyalty to Virginia. The difference in loyalties between the two most important men in her life created a serious moral dilemma for Margaret, one that often strained her relationship with her father.[6] However, Margaret’s ultimate loyalty to the Confederacy demonstrates the strength of her marital allegiance.

The final difficulty in the early years of Margaret’s marriage to J.T.L. was his definition of the proper role of a woman. J.T.L. was a traditional man, and like many others in the antebellum South, he did not believe it was appropriate for a woman to publish her writing. Although he did genuinely enjoy reading his wife’s poems, J.T.L. did not feel comfortable with his wife entering the public sphere, even if only in print. So by his request Margaret stopped writing for the first few years of their marriage.[7]

Civil War Period: A Poet Again

The Civil War provided an interesting set of conditions that ultimately strengthened the marriage between Margaret and J.T.L. in addition to rejuvenating Margaret’s career as a distinguished poet. The war began only a few years after the marriage but they did not let the war ruin their new relationship. The couple had an extensive correspondence while J.T.L. was away at war. Through these letters they were able to demonstrate their love and concern for one another during wartime. Such feelings are reflected in Margaret’s wartime poetry, which she often wrote about her relationship with her husband.

It was through these wartime letters that Margaret’s career resumed. After spending eight months away from home, experiencing the brutality that was the Civil War, J.T.L. wrote a letter to Margaret in which he willed her to use her exceptional literary gift to contribute to the Confederate war effort.[8]

Invoking Civil War imagery, J.T.L. mused, “Would that I may be able to wield my sword when in battle, as you wield your pen!”[9] Grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the confederate cause, Margaret began her career anew; publishing poems that commemorated loved ones and encouraged fortitude.

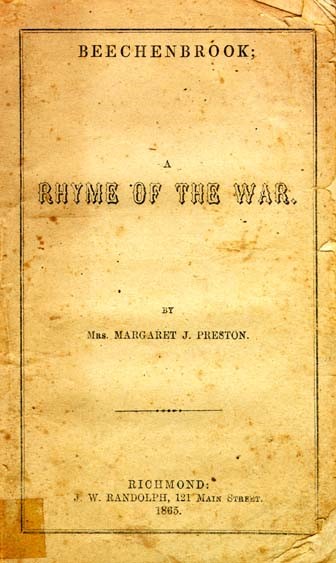

Margaret’s most important wartime publication and the one that truly propelled her to post-war fame, was deeply shaped and informed by the author’s relationship with her husband. J.T.L. spent the harsh winter of 1864 – 1865 in the beleaguered city of Richmond. During this period he sent a letter to his wife with a poem enclosed and commented that he believed she was capable of writing a poem on the same topic, but of much higher quality. Margaret took this complement as an invitation and wrote Beechenbrook: A Rhyme of War in response.

The sixty-four page epic poem, with follows one family through the horrors of the war, was so well-received by J.T.L. and his men that he had the poem published, once during the war, and once again after the war had ended. Margaret’s stepdaughter, Elizabeth Preston Allan, believes that the poem granted its author such success because anyone who had lived through the war in the Confederacy could deeply relate to the experiences Margaret depicted.

By the year 1875, Margaret Junkin Preston was exchanging correspondence with famous men of letters such as Paul Hamilton Hayne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and John Whittier. Her correspondents often wrote to commend her work, as she had become the most distinguished female poet of the South. This success would not have been possible without the education provided by her father and the events of the Civil War, which brought about the support of her husband.

Notes

[1] Stacey J. Klein, Margaret Junkin Preston: Poet of the Confederacy, A Literary Life, University of South Carolina Press, 2007, 4-5.

[2] Mary Price Coulling, “Sonnets, Sauces, and Salvation: The Poetry of Margaret Junkin Preston,” American Presbyterians 73, no. 2 (1995): 101. Accessed October 12, 2015, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23333346

[3] Rev. Dr. T. C. Porter to Elizabeth Preston Allan in Elizabeth Randolph Preston Allan, Life and Letters of Margaret Junkin Preston, (New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1903),24.

[4] Klein, Poet of the Confederacy, 21.

[5] Ibid., 108.

[6] Klein, Poet of the Confederacy, 42.

[7] Allan, Life and Letters, 106.

[8] Kevin J. Hayes, A History of Virginia Literature, Cambridge University Press, 2015, 252.

[9] John Thomas Lewis Preston to Margaret Junkin Preston, 23 December 1861, in Allan, Life and Letters, 126.

[10] Allan, Life and Letters, 98.

Further Reading

Allen, Elizabeth Preston, ed. The Life and Letters of Margaret Junkin Preston. Houghton and Mifflin, 1903.

Hayes, Kevin J. A History of Virginia Literature. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Klein, Stacey J. Margaret Junkin Preston: Poet of the Confederacy, A Literary Life. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2007.

About the project

This page was created as part of an undergraduate research seminar taught in the Virginia Tech History Department by Professor Paul Quigley in Fall 2015. Follow the link to return to the course homepage: The Preston Family: Civil War Experiences.