By Samuel Lee

Civil War medicine is often characterized as gruesome, with unnecessary amputations rampant in unsanitary hospitals both on the battlefield and in the major cities of the Union and Confederacy. Horrific prison conditions are also a commonly thought of characteristic of the Civil War. Prisons such as Andersonville and Castle Thunder have shaped a negative perception of how prisoners were treated by the Confederacy. The horrors of those prisons have been thoroughly researched, but many do not account for the characteristics which contributed to the harsh conditions of hospitals. These characteristics affected not just prisoners of war, but Confederate soldiers themselves.

A Place for Transients: Societal Conceptions of Hospitals in the 1860s

In order to understand how the Confederacy medically treated its prisoners of war, one must first examine the status of medicine within American life in the mid-19th century. Hospitals were not as abundant in the 1860s as they are in the present, and pursuing an education or training to become a doctor, surgeon, or nurse was often viewed as an unsavory career choice. For women, professional medicine was off limits. The public also generally considered hospitals to be strictly for individuals of poor social status and transients. As a result, the number of citizens licensed to practice medicine, as well as the number of hospitals for them to work in, was notably small at the outbreak of the Civil War.

Men were the only ones allowed to be licensed to practice medicine in any capacity. Women, who were typically the primary health care providers in the household at the time, were restricted from providing medical care, and this practice was only disbanded later in the Civil War. By the end of the Civil War, women, most often working as nurses, were commonplace in hospitals in both the Confederacy and the Union.

Ill Equipped, Understaffed, and Unprepared: Medical Preparations of the Confederacy

Due to the lack of doctors at the beginning of the Civil War, most of the hospitals in the United States were understaffed. Additionally, because many Americans considered hospitals an unsavory place to receive medical care, most of the medical staff already employed prior to the war had scant experience in treating wounded or ill. The result was a severely small, undertrained, and inexperienced medical staff treating very severe illnesses and wounds very early in the Civil War.

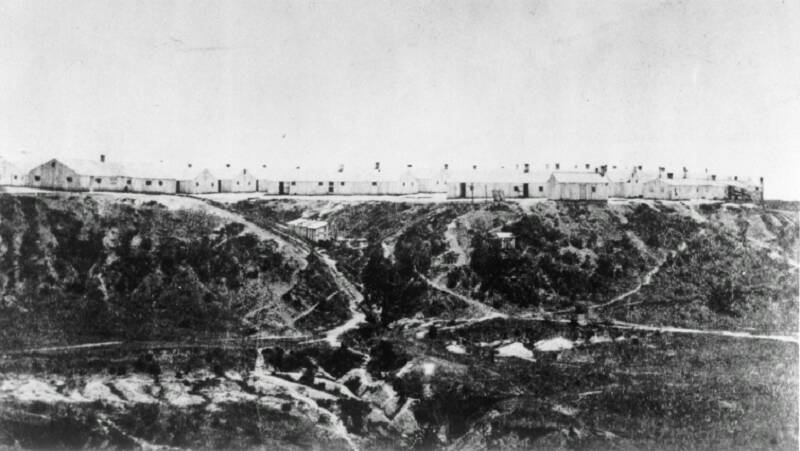

The Confederacy felt this effect far more so than the Union, and this effect was exacerbated as the war progressed less in their favor. For example, at the end of 1863, none of the hospitals surrounding Atlanta contained more than 500 beds for prisoners, soldiers, and civilians; between May and June of 1864, the Atlanta area received over 28,000 admissions into its hospitals, with the majority being for illness rather than wounds.[i] Additionally, a Confederate general order issued in 1862 forbade wounded soldiers from providing any type of assistance in hospitals, placing an extra burden on the medical staff.

The inadequacy of Confederate hospitals and medical supplies led many prisoners of war to feel intentionally mistreated by Confederate surgeons and nurses. One such prisoner, a southern Unionist named John Henning Woods, described what he felt were deliberate attempts to harm his fellow prisoners while being interred at an Atlanta prison. Woods wrote in his diary that one Confederate doctor coldly remarked, “Let them go – they are damned Union men anyhow.”[ii] Woods’ diary entry charged that Confederate officials were deliberately and egregiously allowing prisoners of war to die rather than treat their illnesses and injuries solely on their allegiances alone. However, actual accounts of medical staff in the Confederacy describes a much direr set of circumstances: food and medical supplies were scarce and hospitals were overcrowded and understaffed. Despite these issues, medical staff consistently set aside their ideological differences in order to provide the best care to their prisoners.

Wikimedia Commons)

Through the Eyes of Confederate Nurses and Doctors

Confederate nurses and doctors faced considerable difficulty in providing consistently adequate health care to their patients. The strain of low supplies, worsened by a Union naval blockade on trade in the Confederacy, and consistent overcrowding were common and frequent complaints among Confederate nurses and doctors. Even with these difficulties, a large number of those working in hospitals both on and off the battlefield implored for compassionate treatment of prisoners of war, even though many were vehemently against the Union cause.

For surgeons on the road with the Confederate Army, supply wagons did not always keep pace with the rest of unit. During the Peninsular Campaign, Dr. Spencer Glasgow Welch wrote of being the sole member of his medical unit. Dr. Welch wrote that he could not treat his wounded, because “neither Dr. Kenedy, Dr. Kilgore nor our medical wagon was with us, and I had nothing to give them but morphine.” The wagons and other doctors arrived the next morning.[iii] While never treating a member of the Union Army, Dr. Welch’s letters describe a physician’s frustrations with being unable to treat even his own soldiers due to disorganization and low supplies.

Wikimedia Commons)

A nurse at the Chimborazo Hospital complex In Richmond, Virginia also wrote of the increasing difficulty of providing health care as supplies began to diminish. The nurse, Phoebe Yates Pember, also treated Union prisoners, and wrote of her increasing hunger. Shortages were so severe, Pember wrote, that “almost all the bakeries in the city are closed, and I cannot get my principal means of subsistence – biscuits.”[iv] The lack of food for the medical staff also meant that the likelihood of prisoners and other ailing patients in hospitals were equally unlikely to receive food themselves.

Wikimedia Commons)

Other nurses provided more insight into their feelings regarding treating prisoners of war. Kate Cumming, a Confederate nurse who travelled throughout the South during the war, made her sentiments clear while writing about Unionist prisoners. While visiting the infamous Andersonville prison, Cumming wrote that she “[had] far less respect for these men [southern Unionists] than I have for a real Yankee.”[v] Cumming later provided the prisoners with what supplies she had, ranging from clothes to materials to construct a makeshift kitchen. Conversely, Ada W. Bacot, a nurse in Charlottesville, Virginia during the Peninsular Campaign, felt pity for the wounded and sick Union prisoners. While admitting that she would prefer to not have to treat Union prisoners, Bacot wrote, “I cant [sic] help feeling pity for them, they are human beings.”[vi] Despite their disgust towards Unionists and Union prisoners, these nurses exemplify the majority of those involved in Confederate medicine: strained by a lack of organization and supplies, but refusing to maliciously treat any patient they were provided.

Confederate Medicine: Not Just Andersonville

The vast majority of surgeons, doctors, and nurses of the Confederacy refused to let their own sentiments regarding the Union and the Civil War itself to affect their work. Even without supplies, these medical workers mostly provided the best care they possibly could. Most prisoners were not treated with hatred or even intentionally mistreated. Although the conditions of prisons such as Andersonville are common conceptions of Confederate medicine, the majority of prisoners of war were treated just as well as any other solider.

Further Readings

Freemon, Frank R. Gangrene and Glory: Medical Care during the American Civil War. Chicago: University of Illinois, 2001.

Green, Carol C. Chimborazo: The Confederacy’s Largest Hospital. Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 2004.

Humphreys, Margaret. Marrow of Tragedy: The Health Crisis of the American Civil War. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2013.

Schmidt, James M. and Guy R. Hasegawa. Years of Change and Suffering: Modern Perspectives on Civil War Medicine. Roseville: Edinborough, 2009.

Footnotes

[i] Frank Freemon, Gangrene and Glory: Medical Care During the American Civil War (Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University, 1994), 145-151.

[ii] John Henning Woods Papers Vol. 3, Pg. 12. Ms2017-030, Special Collections, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg Va.

[iii] Spencer Glasgow Welch, 3 September 1862, in In Hospital and Camp: The Civil War Through the Eyes of its Doctors and Nurses, ed. Harold Elk Staubing (Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, 1993), see A Confederate Surgeon’s Letters to His Wife.

[iv] Phoebe Yates Pember, 19 February 1864, in A Southern Woman’s Story: Life in Confederate Richmond, ed. Bell Irvin Wiley (Jackson, Tennessee: McCowat-Mercer Press, 1959), 186.

[v] Kate Cumming, A Journal of Hospital Life in the Confederate Army of Tennessee (Louisville: John P. Morton & Co., 1866), 140.

[vi] Ada W. Bacot, 14 June 1862, in A Confederate Nurse: The Diary of Ada W. Bacot, 1860-1863, ed. Jean V. Berlin (Columbia, South Carolina: Univeristy of South Carolina Press, 1994), 124-125.

About the Project

This page was created as part of an undergraduate research seminar taught in the Virginia Tech History Department by Professor Paul Quigley in Fall 2017. Views and opinions belong to the student authors.

Return to The John Henning Woods Online Exhibit main page.